Ulli Diemer — Radical Digressions

Blogs & Notes

- Notebooks: 10 - 9 - 8 - 7 - 6 - 5 - 4 - 3 - 2 - 1

- Latest Post

- Moments

- Quotes & Fragments

- Scrapbook

- Twitter @ullidiemer

Articles Lists

Thinking about Terry Fox and the Marathon of Hope

Terry Fox dipped his artificial leg into the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Spear on April 12, 1980 and started running west: toward the Pacific. His Marathon of Hope was underway.

Before he set off, he filled two bottles with water from the ocean. They symbolized his hopes: one was to be a souvenir, the other he planned to empty into the Pacific Ocean when he completed his cross-continent run.

Cape Spear, the easternmost point in North America, owes its name to Portuguese fishermen for whom the sight of this desolate windswept promontory represented hope: “Spera” is Portuguese for hope. There is reason for hope when Cape Spear comes into view, as long as you steer clear of the rocks and the icebergs. St. John’s Harbour – sheltered and often 10 degrees warmer than Cape Spear – is only ten kilometers away.

Hope and determination were what fueled Terry Fox when he set off on that cold and blustery morning. He hoped to raise money for cancer research. His goal was to raise one dollar for every Canadian, about $24 million in 1980. More importantly, he wanted to increase awareness of the challenges facing people with cancer and of the need for more research to find treatments and cures. And he wanted to show that having cancer did not preclude hope and taking action for a better world.

His determination grew out of his own experience. In 1977, when he was 18, he was diagnosed with osteosarcoma in his right leg. The leg had to be amputated. Then came learning to walk with an artificial leg, and 16 months of chemotherapy. Like all chemotherapy, it was, as Terry said, a “physically and emotionally draining ordeal.”

The experience changed him. With cancer came empathy. He became increasingly aware of the other people being treated in the cancer clinic, and what they were going through. Later he wrote, “There were faces with the brave smiles, and the ones who had given up smiling. There were feelings of hopeful denial, and the feelings of despair.” And there were those who were no longer there, because all the treatments had failed.

Terry was busy adapting to his new circumstances. Urged on by Rick Hansen, he started playing wheelchair basketball, and in the next three years, helped his team win three national championships.

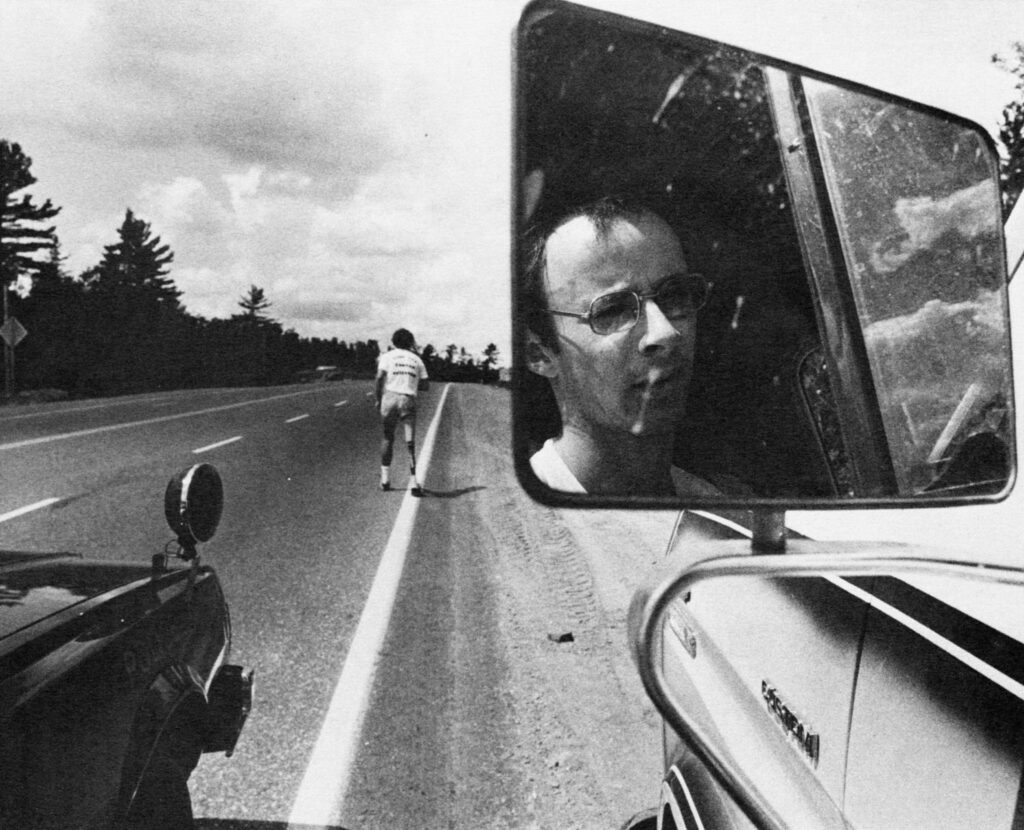

But it wasn’t enough. The people he had encountered in the cancer clinic were always on his mind. He felt he needed to do something. The idea he came up with was a cross-country run, a plan he first confided to his best friend, Doug Alward, who agreed to drive the support van that would be needed. He then pitched the idea to the Canadian Cancer Society, which was skeptical, but ultimately agreed to endorse the venture, as long as he could find sponsors to cover the expenses. Terry found a few sponsors, who donated a van, money for gas, and the shoes he would need. He refused all offers that would have meant endorsing a product or wearing a logo. The Marathon of Hope, the name Terry had chosen, was not to be a vehicle for corporate PR.

*

And so they set off, these two 21-year-olds, Terry running, Doug driving the van which, among other supplies, included two spare artificial legs. The weather was terrible. In the first days, Terry had to deal with a snowstorm, heavy rains, and gale-force winds, with plenty of hills to add to the difficulties. Tough as they were, Terry had known about the physical challenges he would have to face. He had trained hard to prepare himself for this marathon.

The emotional challenges were something else. Looking back, we see Terry Fox as a heroic figure inspiring a whole country, one of the most famous and admired individuals Canada has produced. There are statues and memorials. Millions of people, in more than 60 countries, have taken part in annual Terry Fox Runs. In today’s lazy jargon, he is an ‘icon’ and a ‘legend.’

In April 1980, Terry was an unknown young man running alone along an endless, endless highway. The TransCanada in Newfoundland runs mostly through forest and rock. With a few exceptions, towns are somewhere off the highway, not on the highway. It’s a lonely highway, and it goes on forever. It takes about nine hours to drive from St. John’s to Port aux Basques. It seems inconceivable that someone could run that distance, with one good leg and one artificial leg.

On top of that, the news about the funds being raised was often discouraging. Few people had heard of the Marathon of Hope. There were days when no money at all was raised. But Terry continued to hope that word would spread, and that people would respond when they heard about it. There was no question of quitting. “There can be no reason for me to stop,” Terry said. “No matter what pain I suffer, it is nothing compared to the pain of those who have cancer, of those who endure treatment.”

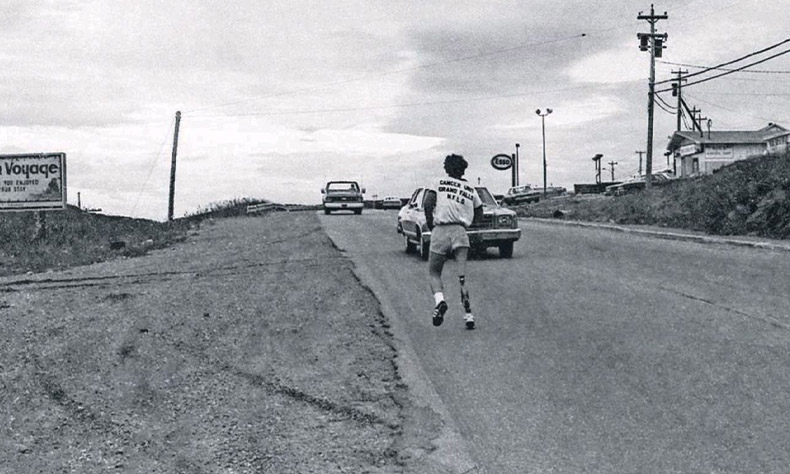

Slowly word spread. In Gambo, people lined up along the highway to see Terry and press money into his hands as he passed by. He was immensely cheered by the response. After Gambo, he started to feel that the Marathon of Hope might take off. In Bishop’s Falls and Grand Falls, people also came out to the highway. Then came Port aux Basques, a town of 4,000 which had raised $10,000. He had now run 882 kilometers. Vancouver was still 6,172 kilometers away.

Terry Fox running into Port aux Basques, May 6, 1980.

*

I don’t much care for the word ‘hero.’ What makes someone a hero? In the past, the word was mostly used to describe individuals who were exceptionally brave in battle, like Horatius at the Bridge, holding off an army that was bent on sacking Rome. But that was 2500 years ago. Today, our heroes are athletes who win gold medals or score lots of goals, feats for which they are often rewarded with multi-million-dollar contracts and corporate sponsorships. And then we have Superheroes – self-righteous, morally repugnant figments of Hollywood’s imagination wreaking havoc on people who are un-American.

The thing is that real-life heroism is not a quality of exceptional individuals, but a quality that is displayed by ordinary people going about their lives. To put it another way, ordinary people are frequently more courageous, and more exceptional, than the ‘heroes’ our culture urges us to admire. Their heroism is manifested, not in an adrenalin-fueled moment in which they confront a crisis, but in a daily struggle to carry on in a world that has dealt them a bad hand. Chekhov said, “Any idiot can face a crisis – it’s day to day living that wears you out.” It’s the people who are worn out and discouraged, but who carry on anyway, as best they can, without anyone to applaud or even witness their courage, who are the heroes of our world.

When I think of people who are exceptionally brave, I think of parents – hundreds of millions around the world – who struggle month after month, year after year, to feed their families. I think of the people of Gaza holding out in the face of a siege that never ends. And, having spent more time than I care to remember in cancer clinics (not as a patient, but accompanying my partner) I, like Terry Fox, think of people undergoing chemotherapy and other treatments.

What I admire most about Terry Fox is precisely his everyday courage. He wasn’t running to be famous, and while he hoped the Marathon of Hope would succeed in raising money for cancer research, he had no inkling of how successful his efforts would ultimately be, let alone that he himself would become famous as a Canadian ‘hero.’ His day-to-day, hour-to-hour, minute-to-minute experience was marked by pain, pain that increased as he went on, and exhaustion. He persevered, like so many other people do despite their burdens, fears, struggles, and loneliness, because that is what life demands of us.

*

Thinking about Terry Fox starting his Marathon of Hope at Cape Spear on this date in 1980 reminds me of another day at Cape Spear. It was 2015, and my partner Miriam and I were on a long road trip through the Atlantic provinces. We were staying in Petty Harbour, just down the road from Cape Spear. It was the middle of July, but it was cold and windy, and there was a big iceberg just offshore. Our photos show us looking windblown but happy. We had reason to be happy. Like Terry, Miriam had had her battles with cancer, but while they had left physical and emotional scars, they were now several years behind her and we were off on our own journey, looking to the future with hope and anticipation.

Miriam hated the corporate nexus of cancer fundraising. She was disgusted by the corporate sponsorships, the scripted phoniness and self-serving PR, and most of all by the ‘pinkwashing’ that has been such a prominent characteristic of breast cancer fundraising in particular. She erupted with rage when the Israeli military painted some of its jets pink to express ‘support’ for women with breast cancer. “The latest grotesqueness” of the pinkwashing campaign, she called it, contemplating the prospect of the Israeli state, which had been denying women in Gaza access to cancer care, subsequently finishing them off by bombing them with pink planes.

Even when she was undergoing chemotherapy for breast cancer herself, Miriam found the energy to protest at how the media covered people with cancer. Breast cancer had become a fashionable cause, and for a time the media were keen to produce stories about women who fit their stereotype of indomitable cancer survivors. Miriam – a physician whose patients were predominantly female and poor – was not impressed, as she indicated in a letter to the Globe and Mail:

“Judging by the Globe and Mail coverage, it appears that breast cancer only strikes women who have six figure incomes, most of whom, apparently, are also high-profile media personalities.

This is not the case. Working-class women and women living in poverty also get breast cancer. These women also face the fear of dying, the worry of how to tell their children and difficult treatment decisions. They do so though with far fewer resources to draw on. Their concerns do not revolve around whether or not to wear a wig during their next television appearance. They are worried about feeding themselves and their children decently during the long ordeals of surgery and chemotherapy. They are challenged by often arduous daily trips to and from radiation appointments that some cannot actually manage. Too sick to work, they struggle to cope with the impact of loss of income on themselves and their families.

Perhaps the Globe and Mail could tear itself away from the concerns of celebrities and devote a story to the realities that these women with breast cancer face.”

Terry Fox’s Marathon of Hope was a different story, as far as Miriam was concerned. She admired Terry for his courage, the empathy that he had developed out of his own experience, and for his insistence that the Terry Fox Runs (which were being organized after the recurrence of his cancer forced him to end his own run) be all-inclusive, non-competitive events with no corporate sponsorships. And she was amazed at how much he had achieved. Aware that she had personally benefited from treatments developed with the help of funds he had raised, she said “If it weren't for Terry Fox, I wouldn't be alive today.”

Terry’s run, begun with such hope at Cape Spear, had ended on a spot on the TransCanada Highway just east of Thunder Bay. He had been ignoring the ever-increasing pain, thinking he could push through it. “Somewhere the hurting must stop,” he believed – but it didn’t. In addition to the pain in his leg, he now had pain in his chest, and suffered coughing fits. Finally, on September 1, he checked into hospital in Thunder Bay. They found that the cancer had returned, and spread to his lungs. On September 2, he told a press conference that after 143 days and 5,373 kilometers, he had to end his run, though he still hoped that he would be able to resume it. Terry flew home to receive chemotherapy, but this time the treatment didn’t work. He died in June of the following year. Before he died, he said “it’s got to keep going without me,” and he worked to make sure it did.

In September 2016, a little over a year after our visit to Cape Spear, the spot where the Marathon of Hope had started, Miriam and I found ourselves at the place where it had ended. We were staying at a bed-and-breakfast nearby, and the woman who ran it told us of standing on the highway with other members of the community on that September day in 1980, the day that was to be the last day of the Marathon of Hope, watching and applauding as Terry went by. Thirty-six years later, it was still a moving memory for her. She urged us to go visit the memorial that had been erected just off the highway at the spot where he stopped.

We did as she suggested. We looked at the monument, contemplated the past, and thought about the future. Much had changed since the preceding year. A few months earlier, we had learned that Miriam’s cancer had returned, and spread through her body. It was now in her lungs and bones. The outlook appeared grim. But even then, she was receiving new treatments which seemed to be making a difference. Recent scans showed that the cancer cells were receding. In the end, the treatments didn’t save her life, but they gave her – gave us – two more years, and some measure of hope that made it easier to go on. Miriam died exactly two years to the day after we visited Terry’s memorial.

*

Terry Fox achieved what he set out to do, and much more besides. His goal had been to raise $24 million – equivalent to $1 for each Canadian. By the time of his death, $23 million had been raised. Since his death, the annual Terry Fox Runs have raised more than $750 million dollars. Another goal had been to raise awareness of the importance of cancer research and treatment: his run certainly accomplished that as well.

Other parts of his legacy are more subtle. Terry Fox called his run the Marathon of Hope. Hope is not an easy thing to define or understand. Hope is not the same as optimism, nor is it a question of ‘positive thinking’ or having a ‘positive attitude.’ Few things are more wrong-headed than advising people with cancer (or any illness) to maintain a ‘positive attitude.’ That is about as helpful as telling someone suffering from depression, or grieving the death of a loved one, to ‘cheer up.’ The ‘positive attitude’ trope easily tips into blaming people for their illness and its outcome: they must have died because they didn’t have a sufficiently positive attitude.

Hope isn’t a passive thing that we have, but something we do. Life is a marathon. It is up to each of us to run that marathon as best we can, and to create hope, for ourselves and others, through our actions, individually and collectively. Terry Fox knew that. The Marathon of Hope goes on.

Ulli Diemer

Doug Alward, in the van, watching Terry run.

This article is also available in German.

Related:

Mighty Moe - book review.